Ancient microbial life on Earth could help us recognize life on other planets, scientists say

FILE - A researcher checks specimens under a microscope. (Chau Doan/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Scientists believe microbes on Earth can help unlock what life was like during the planet’s early stages and this information could potentially help them recognize signs of life on other planets.

Researchers from the University of California in Riverside observed rhodopsin proteins in microbes from all over the world and created a family tree of sorts to distinguish the type of environment archaea (single-celled organisms that can survive in extreme environments) lived in billions of years ago.

"Life as we know it is as much an expression of the conditions on our planet as it is of life itself. We resurrected ancient DNA sequences of one molecule, and it allowed us to link to the biology and environment of the past," said University of Wisconsin-Madison astrobiologist and study lead Betul Kacar.

Scientists hypothesized that microbes from billions of years ago, before the Earth had a protective ozone layer, lived meters below the surface of a primordial ocean and were only capable of absorbing blue and green light to sustain life.

But ever since the Great Oxidation Event over 2 billion years ago, modern microbes have evolved and are able to absorb many colors of light.

"Our study demonstrates for the first time that the behavioral histories of enzymes are amenable to evolutionary reconstruction in ways that conventional molecular biosignatures are not," Kacar said.

How will this help find life on other planets?

Researchers work off the notion that early Earth was essentially an alien environment. It is very different from what we humans (and microbes) experience today.

The Precambrian is the earliest of Earth’s geological ages, according to National Geographic. It spans from the time Earth was created about 4.5 billion years ago until the emergence of multi-celled lifeforms another four billion years later.

During this time, the Earth was covered in a primordial sea which scientists hypothesize is what gave birth to the first single-celled organisms. From there, the Great Oxidation Event took place, allowing an ozone layer to form, making way for multi-celled organisms.

Who’s to say this isn’t happening or could happen on planets circling a distant star not too different from our own?

This recent study will lead the way to potentially helping scientists understand what, if any, life there could be on Earth-like planets or moons in the universe.

"Understanding how organisms here have changed with time and in different environments is going to teach us crucial things about how to search for and recognize life elsewhere," said Edward Schwieterman, an astrobiologist and co-author of the study.

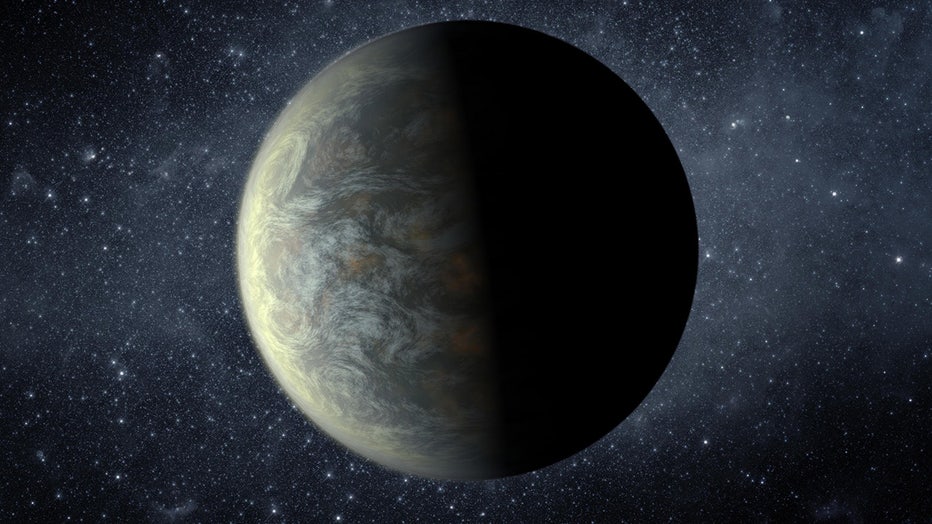

FILE - NASA's Kepler mission has discovered the first Earth-size planets orbiting a sun-like star outside our solar system. The planets, called Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f, are too close to their star to be in the so-called habitable zone where liquid (NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech)

So many planets, so little time

NASA scientists have confirmed the existence of hundreds of new planets outside of our solar system. NASA said 301 exoplanets have been newly validated and added to the total tally of over 5,000 exoplanets.

The discoveries were made thanks to a new machine learning method of differentiating between stars and planets far off in space called ExoMiner.

ExoMiner combs through data previously gathered by NASA’s Kepler and K2 missions to decipher what is and isn’t a planet. The missions gather data on thousands of stars and each one has the potential to host multiple exoplanets.

"It's a hugely time-consuming task to pore over massive datasets. ExoMiner solves this dilemma," NASA said in a news release.

On average, it is estimated that there is at least one planet for every star in the galaxy. That means there's something on the order of billions of planets in our galaxy alone, many in Earth's size range, according to NASA.

NASA said none of the newly-confirmed planets are believed to be Earth-like or habitable.

NASA scientists said now that they have trained ExoMiner using Kepler data, the information learning can be transferred onto other missions.

"There's room to grow," said Hamed Valizadegan, ExoMiner project lead and machine learning manager with the Universities Space Research Association at Ames.

Editor's note: This version of the story has been updated to include the corrected total number of known exoplanets. This story was reported out of Los Angeles; Megan Ziegler contributed.